LZ 127 Graf Zeppelin on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

LZ 127 ''Graf Zeppelin'' () was a German passenger-carrying,

The LZ 127 was designed by

The LZ 127 was designed by  The airship usually took off vertically using static lift (

The airship usually took off vertically using static lift (' s top airspeed was at ; it cruised at , at . It had a total lift capacity of with a usable

The galley staff served three hot meals a day in the main dining and sitting room, which was square. It had four large arched windows, wooden inlays, and

The galley staff served three hot meals a day in the main dining and sitting room, which was square. It had four large arched windows, wooden inlays, and

The main generating plant was in a separate compartment mostly inside the hull. Two

The main generating plant was in a separate compartment mostly inside the hull. Two

The LZ 127 was christened ''Graf Zeppelin'' by Countess Brandenstein-Zeppelin on 8 July 1928, after her father Ferdinand von Zeppelin, the founder of the company, on the 90th anniversary of his birth. During most of its career, it was operated by Luftschiffbau Zeppelin's commercial flight arm,

The LZ 127 was christened ''Graf Zeppelin'' by Countess Brandenstein-Zeppelin on 8 July 1928, after her father Ferdinand von Zeppelin, the founder of the company, on the 90th anniversary of his birth. During most of its career, it was operated by Luftschiffbau Zeppelin's commercial flight arm,

In October 1928, ''Graf Zeppelin'' made its first intercontinental trip, to

In October 1928, ''Graf Zeppelin'' made its first intercontinental trip, to

On 16 May 1929, on the first night of its second trip to the US, ''Graf Zeppelin'' lost four of its engines. With Eckener struggling for a suitable place to force-land, the French Air Ministry allowed him to land at Cuers-Pierrefeu, near

On 16 May 1929, on the first night of its second trip to the US, ''Graf Zeppelin'' lost four of its engines. With Eckener struggling for a suitable place to force-land, the French Air Ministry allowed him to land at Cuers-Pierrefeu, near

The American newspaper publisher

The American newspaper publisher

On 26 April 1930, ''Graf Zeppelin'' flew low over the

On 26 April 1930, ''Graf Zeppelin'' flew low over the

The polar flight (''Polarfahrt 1931'') lasted from 24 to 31 July 1931. The ship rendezvoused with the Soviet icebreaker ''Malygin'', which had the Italian polar explorer

The polar flight (''Polarfahrt 1931'') lasted from 24 to 31 July 1931. The ship rendezvoused with the Soviet icebreaker ''Malygin'', which had the Italian polar explorer

From the beginning, Luftschiffbau Zeppelin had plans to serve South America. There was a large community of Germans in Brazil, and existing sea connections were slow and uncomfortable. ''Graf Zeppelin'' could transport passengers over long distances in the same luxury as an ocean liner, and almost as quickly as contemporary airliners.

''Graf Zeppelin'' made three trips to Brazil in 1931 and nine in 1932. The route to Brazil meant flying down the Rhône valley in France, a cause of great sensitivity between the wars. The French government, concerned about espionage, restricted it to a -wide corridor in 1934. ''Graf Zeppelin'' was too small and slow for the stormy North Atlantic route, but because of the Blau gas fuel, could carry out the longer South Atlantic service. On 2 July 1932 it flew a 24-hour tour of Britain.

From the beginning, Luftschiffbau Zeppelin had plans to serve South America. There was a large community of Germans in Brazil, and existing sea connections were slow and uncomfortable. ''Graf Zeppelin'' could transport passengers over long distances in the same luxury as an ocean liner, and almost as quickly as contemporary airliners.

''Graf Zeppelin'' made three trips to Brazil in 1931 and nine in 1932. The route to Brazil meant flying down the Rhône valley in France, a cause of great sensitivity between the wars. The French government, concerned about espionage, restricted it to a -wide corridor in 1934. ''Graf Zeppelin'' was too small and slow for the stormy North Atlantic route, but because of the Blau gas fuel, could carry out the longer South Atlantic service. On 2 July 1932 it flew a 24-hour tour of Britain.

While returning from Brazil in October 1933, ''Graf Zeppelin'' stopped at NAS Opa Locka in Miami, Florida, and then

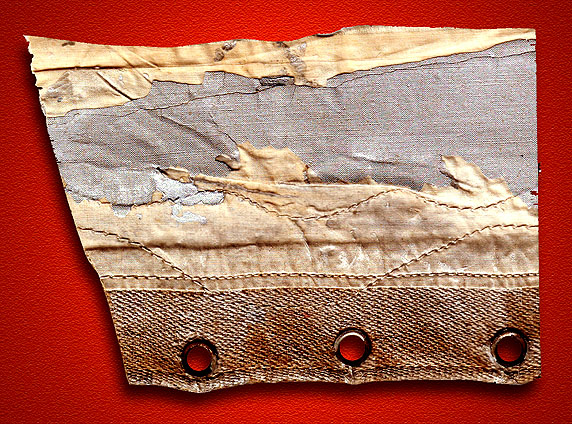

While returning from Brazil in October 1933, ''Graf Zeppelin'' stopped at NAS Opa Locka in Miami, Florida, and then  The airship's cotton envelope absorbed moisture from the air in humid tropical conditions. When the

The airship's cotton envelope absorbed moisture from the air in humid tropical conditions. When the  In late 1935 ''Graf Zeppelin'' operated a temporary postal shuttle service between Recife and Bathurst, in the British African colony of the Gambia. On 24 November, during the second trip, the crew learned of an insurrection in Brazil, and there was some doubt whether it would be possible to return to Recife. ''Graf Zeppelin'' delivered its mail to

In late 1935 ''Graf Zeppelin'' operated a temporary postal shuttle service between Recife and Bathurst, in the British African colony of the Gambia. On 24 November, during the second trip, the crew learned of an insurrection in Brazil, and there was some doubt whether it would be possible to return to Recife. ''Graf Zeppelin'' delivered its mail to  Brazil built a hangar for airships at Bartolomeu de Gusmão Airport, near Rio de Janeiro, at a cost of $1 million (equivalent to $ million in 2018 ). Brazil charged the DZR $2000 ($) per landing, and had agreed that German airships would land there 20 times per year, to pay off the cost. The hangar was constructed in Germany and the parts were transported and assembled on site. It was finished in late 1936, and was used four times by ''Graf Zeppelin'' and five by ''Hindenburg''. It now houses units of the Brazilian Air Force.

''Graf Zeppelin'' made 64 round trips to Brazil, on the first regular intercontinental commercial air passenger service, and it continued until the loss of the ''Hindenburg'' in May 1937.

Brazil built a hangar for airships at Bartolomeu de Gusmão Airport, near Rio de Janeiro, at a cost of $1 million (equivalent to $ million in 2018 ). Brazil charged the DZR $2000 ($) per landing, and had agreed that German airships would land there 20 times per year, to pay off the cost. The hangar was constructed in Germany and the parts were transported and assembled on site. It was finished in late 1936, and was used four times by ''Graf Zeppelin'' and five by ''Hindenburg''. It now houses units of the Brazilian Air Force.

''Graf Zeppelin'' made 64 round trips to Brazil, on the first regular intercontinental commercial air passenger service, and it continued until the loss of the ''Hindenburg'' in May 1937.

' s achievements showed that this was technically possible.

By the time the two ''Graf Zeppelin''s were recycled, they were the last rigid airships in the world, and heavier-than-air long-distance passenger transport, using aircraft like the

British Pathe video clips

San Diego Air & Space Museum: Henry Cord Meyer Collection, Flickr

{{DEFAULTSORT:Lz 127 Graf Zeppelin Graf Zeppelin 1920s German airliners Zeppelins Hydrogen airships 1920s German military reconnaissance aircraft Articles containing video clips

hydrogen

Hydrogen is the chemical element with the symbol H and atomic number 1. Hydrogen is the lightest element. At standard conditions hydrogen is a gas of diatomic molecules having the formula . It is colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-toxic, an ...

-filled rigid airship

A rigid airship is a type of airship (or dirigible) in which the Aerostat, envelope is supported by an internal framework rather than by being kept in shape by the pressure of the lifting gas within the envelope, as in blimps (also called pres ...

that flew from 1928 to 1937. It offered the first commercial transatlantic passenger flight service. Named after the German airship pioneer Ferdinand von Zeppelin

Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin (german: Ferdinand Adolf Heinrich August Graf von Zeppelin; 8 July 1838 – 8 March 1917) was a German general and later inventor of the Zeppelin rigid airships. His name soon became synonymous with airships a ...

, a count () in the German nobility, it was conceived and operated by Dr. Hugo Eckener

Hugo Eckener (10 August 1868 – 14 August 1954) Schwensen Thomas Adam. p. 289 ostsee.de was the manager of the Luftschiffbau Zeppelin during the inter-war years, and also the commander of the famous '' Graf Zeppelin'' for most of its record-set ...

, the chairman of Luftschiffbau Zeppelin

Luftschiffbau Zeppelin GmbH is a German aircraft manufacturing company. It is perhaps best known for its leading role in the design and manufacture of rigid airships, commonly referred to as ''Zeppelins'' due to the company's prominence. The name ...

.

''Graf Zeppelin'' made 590 flights totalling almost 1.7 million kilometres (over 1 million miles). It was operated by a crew of 36, and could carry 24 passengers. It was the longest and largest airship in the world when it was built. It made the first circumnavigation of the world by airship, and the first nonstop crossing of the Pacific Ocean by air; its range was enhanced by its use of Blau gas

Blau gas (german: Blaugas) is an artificial illuminating gas, similar to propane, named after its inventor, Hermann Blau of Augsburg, Germany. Not or rarely used or produced today, it was manufactured by decomposing mineral oils in retorts by ...

as a fuel. It was built using funds raised by public subscription and from the German government, and its operating costs were offset by the sale of special postage stamp

A postage stamp is a small piece of paper issued by a post office, postal administration, or other authorized vendors to customers who pay postage (the cost involved in moving, insuring, or registering mail), who then affix the stamp to the fa ...

s to collectors, the support of the newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst

William Randolph Hearst Sr. (; April 29, 1863 – August 14, 1951) was an American businessman, newspaper publisher, and politician known for developing the nation's largest newspaper chain and media company, Hearst Communications. His flamboya ...

, and cargo and passenger receipts.

After several long flights between 1928 and 1932, including one to the Arctic

The Arctic ( or ) is a polar regions of Earth, polar region located at the northernmost part of Earth. The Arctic consists of the Arctic Ocean, adjacent seas, and parts of Canada (Yukon, Northwest Territories, Nunavut), Danish Realm (Greenla ...

, ''Graf Zeppelin'' provided a commercial passenger and mail service between Germany and Brazil for five years. When the Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right politics, far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that crea ...

came to power, they used it as a propaganda tool. It was withdrawn from service after the Hindenburg disaster

The ''Hindenburg'' disaster was an airship accident that occurred on May 6, 1937, in Manchester Township, New Jersey, United States. The German passenger airship LZ 129 ''Hindenburg'' caught fire and was destroyed during its attemp ...

in 1937, and scrapped for military aircraft production in 1940.

Background

The first successful flight of arigid airship

A rigid airship is a type of airship (or dirigible) in which the Aerostat, envelope is supported by an internal framework rather than by being kept in shape by the pressure of the lifting gas within the envelope, as in blimps (also called pres ...

, Ferdinand von Zeppelin

Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin (german: Ferdinand Adolf Heinrich August Graf von Zeppelin; 8 July 1838 – 8 March 1917) was a German general and later inventor of the Zeppelin rigid airships. His name soon became synonymous with airships a ...

's LZ1, was in Germany in 1900. Between 1910 and 1914, Deutsche Luftschiffahrts-Aktiengesellschaft (DELAG

DELAG, acronym for ''Deutsche Luftschiffahrts-Aktiengesellschaft'' (German for "German Airship Travel Corporation"), was the world's first airline to use an aircraft in revenue service. It operated a fleet of zeppelin rigid airships manufacture ...

) transported thousands of passengers by airship. During World War I, Germany used airships to bomb London and other strategic targets. In 1917, the German LZ 104 (L 59)

Zeppelin LZ 104 (construction number, designated L 59 by the German Imperial Navy) and nicknamed ''Das Afrika-Schiff'' ("The Africa Ship"), was a World War I German dirigible. It is famous for having attempted a long-distance resupply missi ...

was the first airship to make an intercontinental flight, from Jambol in Bulgaria to Khartoum

Khartoum or Khartum ( ; ar, الخرطوم, Al-Khurṭūm, din, Kaartuɔ̈m) is the capital of Sudan. With a population of 5,274,321, its metropolitan area is the largest in Sudan. It is located at the confluence of the White Nile, flowing n ...

and back, a nonstop journey of .

During and just after the war, Britain and the United States built airships, and France and Italy experimented with confiscated German ones. In July 1919 the British R34 R34 may refer to:

* R34 (New York City Subway car)

* R34 (South Africa)

* HM Airship ''R.34'', a rigid airship of the Royal Air Force

* , a destroyer of the Royal Navy

* Nissan Skyline (R34), a mid-size car

* Nissan Skyline GT-R (R34), a sports ca ...

flew from East Fortune

East Fortune is a village in East Lothian, Scotland, located 2 miles (3 km) north west of East Linton. The area is known for its airfield which was constructed in 1915 to help protect Britain from attack by German Zeppelin airships during t ...

in Scotland to New York and back. Luftschiffbau Zeppelin

Luftschiffbau Zeppelin GmbH is a German aircraft manufacturing company. It is perhaps best known for its leading role in the design and manufacture of rigid airships, commonly referred to as ''Zeppelins'' due to the company's prominence. The name ...

delivered LZ 126 to the US Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

as a war reparation

War reparations are compensation payments made after a war by one side to the other. They are intended to cover damage or injury inflicted during a war.

History

Making one party pay a war indemnity is a common practice with a long history.

R ...

in October 1924. The company chairman Dr. Hugo Eckener commanded the delivery flight, and the ship was commissioned as the USS ''Los Angeles'' (ZR-3).

The Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June ...

had placed limits on German aviation; in 1925, when the Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

relaxed the restrictions, Eckener saw the chance to start an intercontinental air passenger service, and began lobbying the government for funds and permission to build a new civil airship. Public subscription raised (the equivalent of US$

The United States dollar (symbol: $; code: USD; also abbreviated US$ or U.S. Dollar, to distinguish it from other dollar-denominated currencies; referred to as the dollar, U.S. dollar, American dollar, or colloquially buck) is the official ...

600,000 at the time, or $ million in 2018 dollars), and the government granted over ($ million).

Design and operation

The LZ 127 was designed by

The LZ 127 was designed by Ludwig Dürr

Ludwig Dürr (4 June 1878 in Stuttgart – 1 January 1956 in Friedrichshafen) was a German airship designer.

Life and career

After completing training as a mechanic, Dürr continued his training at the Königliche Baugewerkschule (Royal School ...

as a "stretched" version of the zeppelin LZ 126 rechristened the USS ''Los Angeles''). It was intended from the beginning as a technology demonstrator for the more capable airships that would follow. It was built between 1926 and September 1928 at the Luftschiffbau Zeppelin works in Friedrichshafen

Friedrichshafen ( or ; Low Alemannic: ''Hafe'' or ''Fridrichshafe'') is a city on the northern shoreline of Lake Constance (the ''Bodensee'') in Southern Germany, near the borders of both Switzerland and Austria. It is the district capital (''K ...

, on Lake Constance

Lake Constance (german: Bodensee, ) refers to three Body of water, bodies of water on the Rhine at the northern foot of the Alps: Upper Lake Constance (''Obersee''), Lower Lake Constance (''Untersee''), and a connecting stretch of the Rhine, ca ...

, Germany, which became its home port for nearly all of its flights. Its duralumin

Duralumin (also called duraluminum, duraluminium, duralum, dural(l)ium, or dural) is a trade name for one of the earliest types of age-hardenable aluminium alloys. The term is a combination of '' Dürener'' and ''aluminium''.

Its use as a tra ...

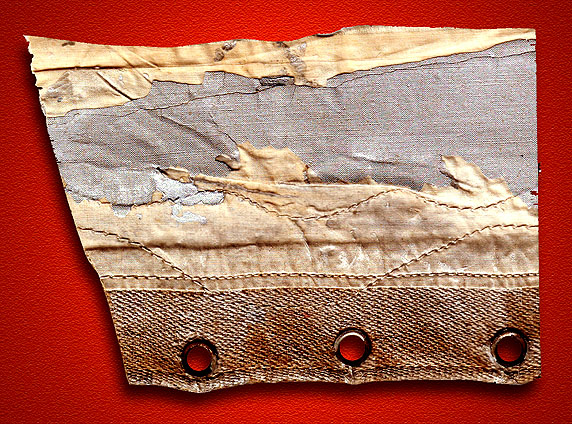

frame was made of eighteen 28-sided structural polygons joined lengthwise with of girders and braced with steel wire. The outer cover was of thick cotton

Cotton is a soft, fluffy staple fiber that grows in a boll, or protective case, around the seeds of the cotton plants of the genus ''Gossypium'' in the mallow family Malvaceae. The fiber is almost pure cellulose, and can contain minor perce ...

, painted with aircraft dope containing aluminium to reduce solar heating, then sandpapered smooth. The gas cells were also cotton, lined with goldbeater's skin

Goldbeater's skin is the processed outer membrane of the intestine of an animal, typically cattle, which is valued for its strength against tearing. The term derives from its traditional use as durable layers interleaved between sheets of gold st ...

s, and protected from damage by a layer containing of ramie

Ramie (pronounced: , ; from Malay ) is a flowering plant in the nettle family Urticaceae, native to eastern Asia. It is a herbaceous perennial growing to tall;

fibre.

''Graf Zeppelin'' was long and had a total gas volume of , of which was hydrogen carried in 17 lifting gas

A lifting gas or lighter-than-air gas is a gas that has a density lower than normal atmospheric gases and rises above them as a result. It is required for aerostats to create buoyancy, particularly in lighter-than-air aircraft, which include ballo ...

cells (''Traggaszelle''), and was Blau gas

Blau gas (german: Blaugas) is an artificial illuminating gas, similar to propane, named after its inventor, Hermann Blau of Augsburg, Germany. Not or rarely used or produced today, it was manufactured by decomposing mineral oils in retorts by ...

in 12 fuel gas cells (''Kraftgaszelle''). The ''Graf Zeppelin'' was built to be the largest possible airship that could fit into the company's construction hangar, with only between the top of the finished vessel and the hangar roof. It was the longest and most voluminous airship when built, but it was too slender for optimum aerodynamic efficiency, and there were worries that the shape would compromise its strength.

''Graf Zeppelin'' was powered by five Maybach VL II

The Maybach VL II was a type of internal combustion engine built by the German company Maybach in the late 1920s and 1930s. It was an uprated development of the successful Maybach VL I, and like the VL I, was a 60° V-12 engine.

Five of them powe ...

12-cylinder engines, each of capacity, mounted in individual streamlined nacelle

A nacelle ( ) is a "streamlined body, sized according to what it contains", such as an engine, fuel, or equipment on an aircraft. When attached by a pylon entirely outside the airframe, it is sometimes called a pod, in which case it is attached ...

s arranged so that each was in an undisturbed airflow. The engines were reversible, and were monitored by crew members who accessed them during flight via open ladders. The two-bladed wooden pusher propellers were in diameter, and were later upgraded to four-bladed units. On longer flights, the ''Graf Zeppelin'' often flew with one engine shut down to conserve fuel.

''Graf Zeppelin'' was the only rigid airship to burn Blau gas

Blau gas (german: Blaugas) is an artificial illuminating gas, similar to propane, named after its inventor, Hermann Blau of Augsburg, Germany. Not or rarely used or produced today, it was manufactured by decomposing mineral oils in retorts by ...

; the engines were started on petrol

Gasoline (; ) or petrol (; ) (see ) is a transparent, petroleum-derived flammable liquid that is used primarily as a fuel in most spark-ignited internal combustion engines (also known as petrol engines). It consists mostly of organic c ...

and could then switch fuel. A liquid-fuelled airship loses weight as it burns fuel, requiring the release of lifting gas, or the capture of water from exhaust gas or rainfall, to avoid the vessel climbing. Blau gas was only slightly heavier than air, so burning it had little effect on buoyancy. On a typical transatlantic journey, the ''Graf Zeppelin'' used Blau gas 90% of the time, only burning petrol if the ship was too heavy, and used ten times less hydrogen per day than the smaller zeppelin ''L 59'' did on its Khartoum

Khartoum or Khartum ( ; ar, الخرطوم, Al-Khurṭūm, din, Kaartuɔ̈m) is the capital of Sudan. With a population of 5,274,321, its metropolitan area is the largest in Sudan. It is located at the confluence of the White Nile, flowing n ...

flight in 1917.

''Graf Zeppelin'' typically carried of ballast

Ballast is material that is used to provide stability to a vehicle or structure. Ballast, other than cargo, may be placed in a vehicle, often a ship or the gondola of a balloon or airship, to provide stability. A compartment within a boat, ship ...

water and of spare parts, including an extra propeller. Calcium chloride

Calcium chloride is an inorganic compound, a salt with the chemical formula . It is a white crystalline solid at room temperature, and it is highly soluble in water. It can be created by neutralising hydrochloric acid with calcium hydroxide.

Ca ...

was added to the ballast water to prevent freezing. The ship retained grey water

Greywater (or grey water, sullage, also spelled gray water in the United States) refers to domestic wastewater generated in households or office buildings from streams without fecal contamination, i.e., all streams except for the wastewater fro ...

from the sinks for use as additional ballast. Both fresh and waste water could be moved forward and aft to control trim.

The airship usually took off vertically using static lift (

The airship usually took off vertically using static lift (buoyancy

Buoyancy (), or upthrust, is an upward force exerted by a fluid that opposes the weight of a partially or fully immersed object. In a column of fluid, pressure increases with depth as a result of the weight of the overlying fluid. Thus the p ...

), then started the engines in the air, adding aerodynamic lift

A fluid flowing around an object exerts a force on it. Lift is the component of this force that is perpendicular to the oncoming flow direction. It contrasts with the drag force, which is the component of the force parallel to the flow direc ...

. Normal cruising altitude was ; it climbed if necessary to cross high ground or poor weather, and often descended in stormy weather. To measure the wind speed over the sea, and calculate drift, floating pyrotechnic flare

A flare, also sometimes called a fusée, fusee, or bengala in some Latin-speaking countries, is a type of pyrotechnic that produces a bright light or intense heat without an explosion. Flares are used for distress signaling, illumination, ...

s were dropped.

When preparing to land the crew advised the ground, either by radio or signal flag

Flag signals can mean any of various methods of using flags or pennants to send signals. Flags may have individual significance as signals, or two or more flags may be manipulated so that their relative positions convey symbols. Flag signals allo ...

. Ground crew lit a smoky fire, to help the airshipmen judge wind speed and direction. The airship slowed, then adjusted buoyancy to neutral by valving off hydrogen or dropping ballast. Echo sounding

Echo sounding or depth sounding is the use of sonar for ranging, normally to determine the depth of water (bathymetry). It involves transmitting acoustic waves into water and recording the time interval between emission and return of a pulse; ...

with the report from an 11-mm blank round

A blank is a firearm cartridge that, when fired, does not shoot a projectile like a bullet or pellet, but generates a muzzle flash and an explosive sound ( muzzle report) like a normal gunshot would. Firearms may need to be modified to allow a bl ...

was used to measure altitude accurately. The ship flew in with its nose trimmed slightly down, made its final approach

In aeronautics, the final approach (also called the final leg and final approach leg) is the last leg in an aircraft's approach to landing, when the aircraft is lined up with the runway and descending for landing.Crane, Dale: ''Dictionary of ...

into the wind descending at per minute, then used reverse thrust

Thrust reversal, also called reverse thrust, is the temporary diversion of an aircraft engine's thrust for it to act against the forward travel of the aircraft, providing deceleration. Thrust reverser systems are featured on many jet aircraft to ...

to stop over the landing flag, where it dropped ropes to the ground. Landing in rough weather required a faster approach. Up to 300 people manhandled the airship into a hangar or secured it by the nose to a mooring mast.

''Graf Zeppelin''payload

Payload is the object or the entity which is being carried by an aircraft or launch vehicle. Sometimes payload also refers to the carrying capacity of an aircraft or launch vehicle, usually measured in terms of weight. Depending on the nature of ...

of on a flight. It was slightly unstable in yaw, and to make it easier to fly, had an automatic pilot which stabilised it in that axis. Pitch was controlled manually by an elevatorman who tried to limit the angle to 5° up or down, so as not to upset the bottles of wine which accompanied the elaborate food served on board. Operating the elevators was so demanding and strenuous that an elevatorman's shift was only four hours, reduced to two in rough weather.

Layout

The operational spaces, common areas, and passenger cabins were built into a gondola structure in the forward part of the airship's ventral surface, with the flight deck well forward in a "chin" position. The gondola was long and wide; its streamlined design reflected contemporary aesthetics, minimised overall height, and reduced drag. Behind the flight deck was the map room, with two large hatches to allow the command crew to communicate with the navigators, who could take readings with a sextant through the two large windows. There was also a radio room and agalley

A galley is a type of ship that is propelled mainly by oars. The galley is characterized by its long, slender hull, shallow draft, and low freeboard (clearance between sea and gunwale). Virtually all types of galleys had sails that could be used ...

with a double electric oven and hot plates.

The galley staff served three hot meals a day in the main dining and sitting room, which was square. It had four large arched windows, wooden inlays, and

The galley staff served three hot meals a day in the main dining and sitting room, which was square. It had four large arched windows, wooden inlays, and Art Deco

Art Deco, short for the French ''Arts Décoratifs'', and sometimes just called Deco, is a style of visual arts, architecture, and product design, that first appeared in France in the 1910s (just before World War I), and flourished in the Unite ...

-upholstered furniture. Between meals, the passengers could socialise and look at the scenery. On the round-the-world flight, there was dancing to a phonograph

A phonograph, in its later forms also called a gramophone (as a trademark since 1887, as a generic name in the UK since 1910) or since the 1940s called a record player, or more recently a turntable, is a device for the mechanical and analogu ...

, fine wine, and Ernst Lehmann

Captain Ernst August Lehmann (12 May 1886 – 7 May 1937) was a German Zeppelin captain. He was one of the most famous and experienced figures in German airship travel. The ''Pittsburgh Press'' called Lehmann the best airship pilot in the world ...

, one of the officers, played the accordion

Accordions (from 19th-century German ''Akkordeon'', from ''Akkord''—"musical chord, concord of sounds") are a family of box-shaped musical instruments of the bellows-driven free-reed aerophone type (producing sound as air flows past a reed ...

. A corridor led to ten passenger cabins capable of sleeping 24, a pair of washrooms, and dual chemical toilet

A chemical toilet collects human excreta in a holding tank and uses chemicals to minimize odors. They do not require a connection to a water supply and are used in a variety of situations. These toilets are usually, but not always, self-containe ...

s. The passenger cabins were set by day with a sofa, which converted at night into two beds. The cabins were often cold, and on some sectors passengers wore furs and huddled under blankets to stay warm. There was a noticeable smell from the Blau gas, especially when the ship was stationary.

A ladder from the map room led up to the keel corridor inside the hull, and accommodation for the 36 crewmen. Officers' quarters were towards the nose; behind them were the baggage store, the crew mess-room, and the quarters for the ordinary crew, who slept in wire-frame beds with fabric screens. Also along this corridor were petrol, oil and water tanks, and stowage for cargo and spare parts. Branches from the keel corridor led to the five engine nacelles, and there were ladders up to the axial corridor, just below the ship's main axis, which gave access to all the gas cells.

Electrical and communications systems

The main generating plant was in a separate compartment mostly inside the hull. Two

The main generating plant was in a separate compartment mostly inside the hull. Two Wanderer

Wanderer, Wanderers, or The Wanderer may refer to:

* Nomadism, Nomadic and/or itinerant people, working short-term before moving to other locations, who wander from place to place with no permanent home, or are vagrancy (people), vagrant

* The Wan ...

car engines adapted to burn Blau gas, only one of which operated at a time, drove two Siemens & Halske

Siemens & Halske AG (or Siemens-Halske) was a German electrical engineering company that later became part of Siemens.

It was founded on 12 October 1847 as ''Telegraphen-Bauanstalt von Siemens & Halske'' by Werner von Siemens and Johann Ge ...

dynamos each. One dynamo on each engine powered the oven and hotplates, and one the lighting and gyrocompass

A gyrocompass is a type of non-magnetic compass which is based on a fast-spinning disc and the rotation of the Earth (or another planetary body if used elsewhere in the universe) to find geographical direction automatically. The use of a gyroc ...

. Cooling water from these engines heated radiators inside the passenger lounge. Two ram air turbine

A ram air turbine (RAT) is a small wind turbine that is connected to a hydraulic pump, or electrical generator, installed in an aircraft and used as a power source. The RAT generates power from the airstream by ram pressure due to the speed o ...

s attached to the main gondola on swinging arms provided electrical power for the radio room, internal lighting, and the galley. Batteries could power essential services like radios for half an hour, and there were small petrol generators for emergency power.

Three radio operators used a one-kilowatt vacuum tube

A vacuum tube, electron tube, valve (British usage), or tube (North America), is a device that controls electric current flow in a high vacuum between electrodes to which an electric voltage, potential difference has been applied.

The type kn ...

transmitter (about 140 W antenna power) to send telegrams over the low frequency (500–3,000 m) bands. A 70 W antenna power emergency transmitter carried telegraph and radio telephone signals over 300–1,300 m wavelength bands. The main aerial consisted of two lead

Lead is a chemical element with the symbol Pb (from the Latin ) and atomic number 82. It is a heavy metal that is denser than most common materials. Lead is soft and malleable, and also has a relatively low melting point. When freshly cu ...

-weighted -long wires deployed by electric motor or hand crank; the emergency aerial was a wire stretched from a ring on the hull. Three six-tube receivers served the wavelengths from 120 to 1,200 m (medium frequency

Medium frequency (MF) is the ITU designation for radio frequencies (RF) in the range of 300 kilohertz (kHz) to 3 megahertz (MHz). Part of this band is the medium wave (MW) AM broadcast band. The MF band is also known as the ...

), 400 to 4,000 m (low frequency) and 3,000 to 25,000 m (overlapping low frequency and very low frequency

Very low frequency or VLF is the ITU designation for radio frequencies (RF) in the range of 3–30 kHz, corresponding to wavelengths from 100 to 10 km, respectively. The band is also known as the myriameter band or myriameter wave a ...

). The radio room also had a shortwave receiver

A shortwave radio receiver is a radio receiver that can receive one or more shortwave bands, between 1.6 and 30 MHz. A shortwave radio receiver often receives other broadcast bands, such as FM radio, Longwave and Mediumwave. Shortwave radio recei ...

for 10 to 280 m (high frequency

High frequency (HF) is the ITU designation for the range of radio frequency electromagnetic waves (radio waves) between 3 and 30 megahertz (MHz). It is also known as the decameter band or decameter wave as its wavelengths range from one to ten ...

).

A radio direction finder used a loop antenna to determine the airship's bearing from any two land radio stations or ships with known positions. During the first transatlantic flight in 1928, the radio room sent 484 private telegram

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas p ...

s and 160 press telegrams.

Operational history

The LZ 127 was christened ''Graf Zeppelin'' by Countess Brandenstein-Zeppelin on 8 July 1928, after her father Ferdinand von Zeppelin, the founder of the company, on the 90th anniversary of his birth. During most of its career, it was operated by Luftschiffbau Zeppelin's commercial flight arm,

The LZ 127 was christened ''Graf Zeppelin'' by Countess Brandenstein-Zeppelin on 8 July 1928, after her father Ferdinand von Zeppelin, the founder of the company, on the 90th anniversary of his birth. During most of its career, it was operated by Luftschiffbau Zeppelin's commercial flight arm, DELAG

DELAG, acronym for ''Deutsche Luftschiffahrts-Aktiengesellschaft'' (German for "German Airship Travel Corporation"), was the world's first airline to use an aircraft in revenue service. It operated a fleet of zeppelin rigid airships manufacture ...

, in conjunction with the Hamburg-American Line (HAPAG); for its final two years it flew for the Deutsche Zeppelin Reederei

Deutsche Zeppelin-Reederei (), abbreviated DZR, is a German limited-liability company that operates commercial passenger zeppelin flights. The current incarnation of the DZR was founded in 2001 and is based in Friedrichshafen. It is a subsidiary ...

(DZR).

Passengers paid premium fares to fly on the ''Graf Zeppelin'' ( from Germany to Rio de Janeiro

Rio de Janeiro ( , , ; literally 'River of January'), or simply Rio, is the capital of the state of the same name, Brazil's third-most populous state, and the second-most populous city in Brazil, after São Paulo. Listed by the GaWC as a b ...

in 1934, equal to $590 then, or $ in 2018 dollars), and fees collected for valuable freight and air mail also provided income. On the first transatlantic flight, ''Graf Zeppelin'' carried 66,000 postcards and covers.

Eckener had earned his doctorate in Psychology

Psychology is the scientific study of mind and behavior. Psychology includes the study of conscious and unconscious phenomena, including feelings and thoughts. It is an academic discipline of immense scope, crossing the boundaries betwe ...

at Leipzig University

Leipzig University (german: Universität Leipzig), in Leipzig in Saxony, Germany, is one of the world's oldest universities and the second-oldest university (by consecutive years of existence) in Germany. The university was founded on 2 December ...

under Wilhelm Wundt, and could use his knowledge of mass psychology to the benefit of the ''Graf Zeppelin''. He identified safety as the most important factor in the ship's public acceptance, and was ruthless in pursuit of this. He took complete responsibility for the ship, from technical matters, to finance, to arranging where it would fly next on its years-long public relations campaign, in which he promoted "zeppelin fever". On one of the Brazil trips British Pathé News

Pathé News was a producer of newsreels and documentaries from 1910 to 1970 in the United Kingdom. Its founder, Charles Pathé, was a pioneer of moving pictures in the silent era. The Pathé News archive is known today as British Pathé. Its col ...

filmed on board. Eckener cultivated the press, and was gratified when the British journalist Lady Grace Drummond-Hay wrote, and millions read, that:

''Graf Zeppelin'' was greeted by large crowds on most of its early voyages. There were 100,000 at Moscow and possibly 250,000 at Tokyo to see it. At Stockholm, spectators launched firework rockets around it, and on the return flight from Moscow it was punctured by rifle shots near the Soviet Union-Lithuania border. On one visit to Rio de Janeiro people released hundreds of small toy petrol-burning hot air balloons near the flammable craft. The airship captured the public imagination and was used extensively in advertising. On visits to England, it photographed Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and ...

bases, the Blackburn aircraft

Blackburn () is an industrial town and the administrative centre of the Blackburn with Darwen borough in Lancashire, England. The town is north of the West Pennine Moors on the southern edge of the Ribble Valley, east of Preston and north- ...

factory in Yorkshire, and the Portsmouth naval dockyard; it is likely that this was espionage

Espionage, spying, or intelligence gathering is the act of obtaining secret or confidential information (intelligence) from non-disclosed sources or divulging of the same without the permission of the holder of the information for a tangibl ...

at the behest of the German government.

Proving flights

During 1928, there were six proving flights. On the fourth one, Blau gas was used for the first time. ''Graf Zeppelin'' carriedOskar von Miller

Oskar von Miller (7 May 1855 – 9 April 1934) was a German engineer and founder of the Deutsches Museum, a large museum of technology and science in Munich.

Biography

Born in Munich into an Upper Bavarian family from Aichach, he was the son of ...

, head of the Deutsches Museum

The Deutsches Museum (''German Museum'', officially (English: ''German Museum of Masterpieces of Science and Technology'')) in Munich, Germany, is the world's largest museum of science and technology, with about 28,000 exhibited objects from ...

; Charles E. Rosendahl, commander of USS ''Los Angeles''; and the British airshipmen Ralph Sleigh Booth and George Herbert Scott. It flew from Friedrichshafen to Ulm

Ulm () is a city in the German state of Baden-Württemberg, situated on the river Danube on the border with Bavaria. The city, which has an estimated population of more than 126,000 (2018), forms an urban district of its own (german: link=no, ...

, via Cologne

Cologne ( ; german: Köln ; ksh, Kölle ) is the largest city of the German western States of Germany, state of North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW) and the List of cities in Germany by population, fourth-most populous city of Germany with 1.1 m ...

and across the Netherlands to Lowestoft in England, then home via Bremen

Bremen (Low German also: ''Breem'' or ''Bräm''), officially the City Municipality of Bremen (german: Stadtgemeinde Bremen, ), is the capital of the German state Free Hanseatic City of Bremen (''Freie Hansestadt Bremen''), a two-city-state consis ...

, Hamburg

(male), (female) en, Hamburger(s),

Hamburgian(s)

, timezone1 = Central (CET)

, utc_offset1 = +1

, timezone1_DST = Central (CEST)

, utc_offset1_DST = +2

, postal ...

, Berlin, Leipzig

Leipzig ( , ; Upper Saxon: ) is the most populous city in the German state of Saxony. Leipzig's population of 605,407 inhabitants (1.1 million in the larger urban zone) as of 2021 places the city as Germany's eighth most populous, as wel ...

and Dresden

Dresden (, ; Upper Saxon: ''Dräsdn''; wen, label=Upper Sorbian, Drježdźany) is the capital city of the German state of Saxony and its second most populous city, after Leipzig. It is the 12th most populous city of Germany, the fourth larg ...

, a total of in 34 hours and 30 minutes. On the fifth flight, Eckener caused a minor controversy by flying close to Huis Doorn

Huis Doorn (; en, Doorn Manor) is a manor house and national museum in the town of Doorn in the Netherlands. The residence has early 20th-century interiors from the time when former German Emperor Wilhelm II resided there (1919–1941).

Huis Do ...

in the Netherlands, which some interpreted as a gesture of support for the former Kaiser Wilhelm II

, house = Hohenzollern

, father = Frederick III, German Emperor

, mother = Victoria, Princess Royal

, religion = Lutheranism (Prussian United)

, signature = Wilhelm II, German Emperor Signature-.svg

Wilhelm II (Friedrich Wilhelm Viktor ...

who was living in exile there.

First intercontinental flight (1928)

In October 1928, ''Graf Zeppelin'' made its first intercontinental trip, to

In October 1928, ''Graf Zeppelin'' made its first intercontinental trip, to Lakehurst Naval Air Station

Lakehurst Maxfield Field, formerly known as Naval Air Engineering Station Lakehurst (NAES Lakehurst), is the naval component of Joint Base McGuire–Dix–Lakehurst (JB MDL), a United States Air Force-managed joint base headquartered approximately ...

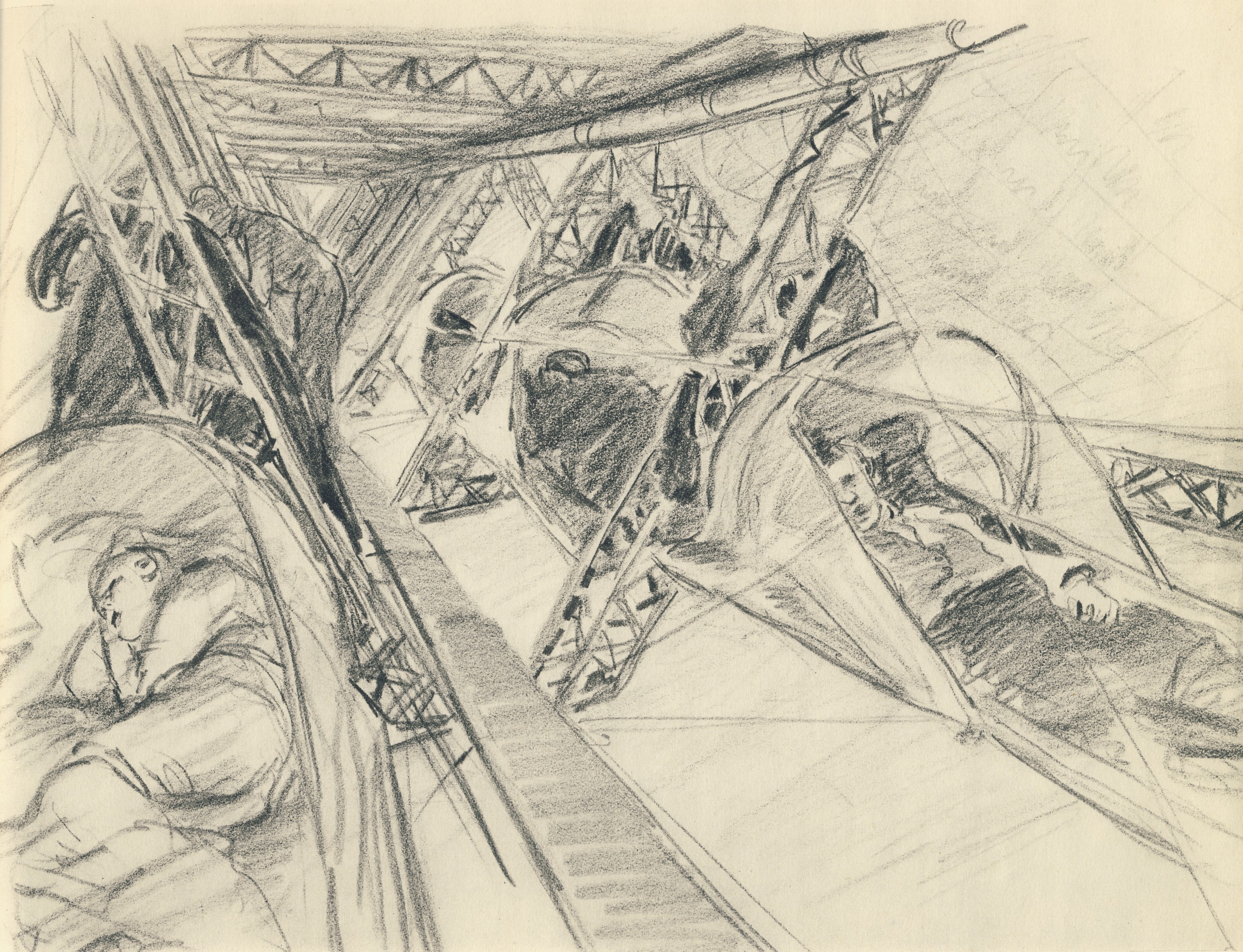

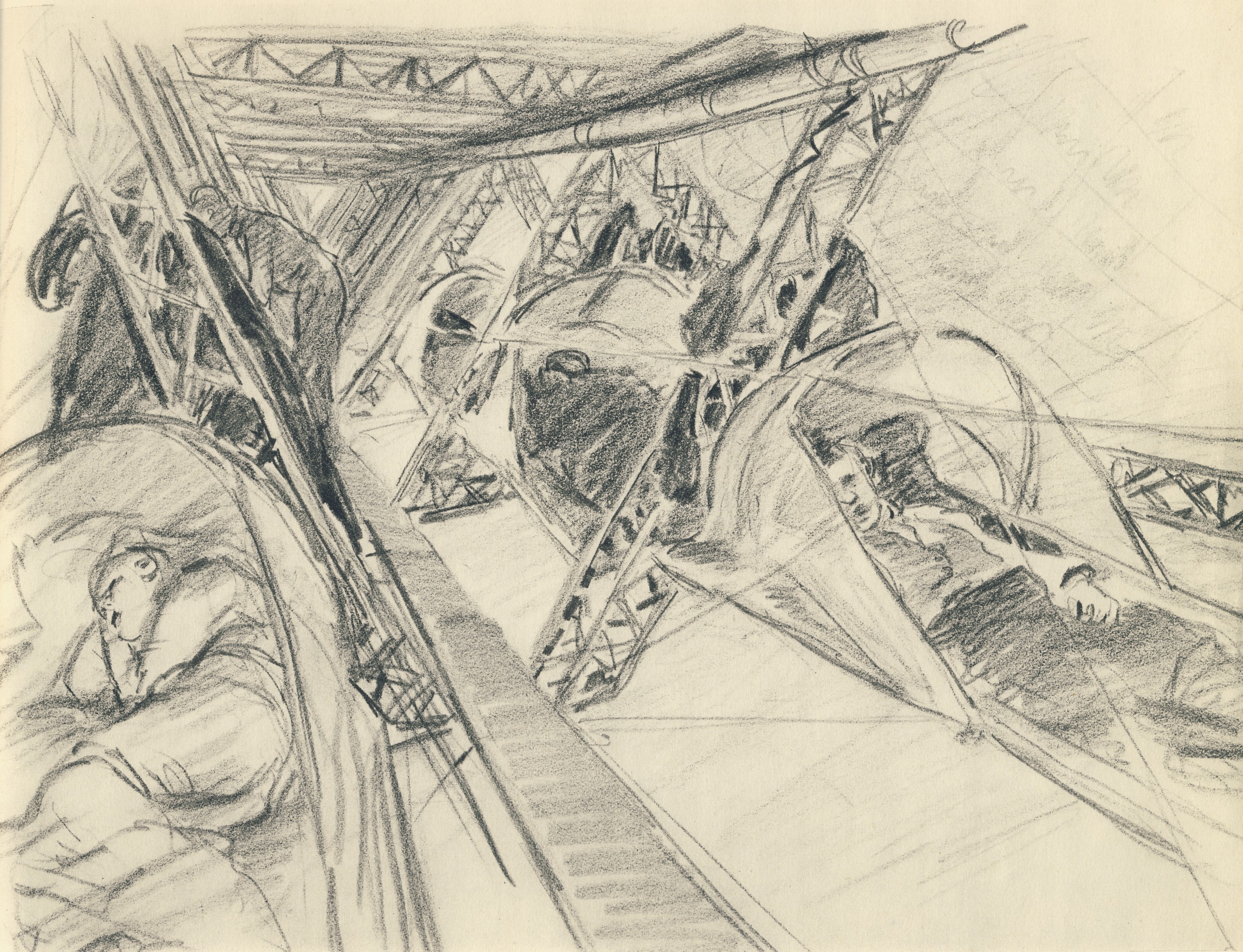

, New Jersey, US, with Eckener in command and Lehmann as first officer. Rosendahl and Drummond-Hay flew the outward leg. Ludwig Dettmann

Ludwig Julius Christian Dettmann (25 July 1865 – 19 November 1944) was a German Impressionism, Impressionist painter. Shortly before his death, he was added to the ''Gottbegnadeten list, Gottbegnadeten'' list, a roster of artists considered cruc ...

and Theo Matejko

Theo Matejko (18 June 1893 – 9 September 1946) was an Austrian illustrator. He served in World War I and covered racing car events. In October 1928, with Ludwig Dettmann, he was invited on the first transatlantic flight of the airship ''Graf ...

made an artistic record of the flight.

On the third day of the flight, a large section of the fabric covering of the port tail fin was damaged while passing through a mid-ocean squall line

A squall line, or more accurately a quasi-linear convective system (QLCS), is a line of thunderstorms, often forming along or ahead of a cold front. In the early 20th century, the term was used as a synonym for cold front (which often are accom ...

, and volunteer riggers (including Eckener's son, Knut) repaired the torn fabric. Eckener directed Rosendahl to make a distress call

A distress signal, also known as a distress call, is an internationally recognized means for obtaining help. Distress signals are communicated by transmitting radio signals, displaying a visually observable item or illumination, or making a soun ...

; when this was received, and nothing else was heard from the airship, many believed it was lost. After the ship arrived safely, there was some annoyance from the Lakehurst personnel that it had not answered repeated calls for its position and estimated arrival time. The crossing, the longest non-stop flight at the time, had taken 111 hours 44 minutes.

Clara Adams

Clara Adams (born Clara Grabau; 1884 – 1971), known as the "first flighter" and the "maiden of maiden flights," was an aircraft passenger and enthusiast who set a variety of flying records. She helped popularize air travel and was the first woma ...

became the first female paying passenger to fly transatlantic on the return flight. The ship endured an overnight gale that blew it backwards in the air and off course, to the coast of Newfoundland. A stowaway boarded at Lakehurst and was discovered in the mail room mid-voyage. The airship returned home and on 6 November flew to Berlin Staaken, where it was met by the German president, Paul von Hindenburg

Paul Ludwig Hans Anton von Beneckendorff und von Hindenburg (; abbreviated ; 2 October 1847 – 2 August 1934) was a German field marshal and statesman who led the Imperial German Army during World War I and later became President of Germany fr ...

.

Mediterranean flights (1929)

''Graf Zeppelin'' visited Palestine in late March 1929. At Rome it sent greetings toBenito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in 194 ...

and King Victor Emmanuel III

The name Victor or Viktor may refer to:

* Victor (name), including a list of people with the given name, mononym, or surname

Arts and entertainment

Film

* ''Victor'' (1951 film), a French drama film

* ''Victor'' (1993 film), a French shor ...

. It entered Palestine, flew over Tel Aviv

Tel Aviv-Yafo ( he, תֵּל־אָבִיב-יָפוֹ, translit=Tēl-ʾĀvīv-Yāfō ; ar, تَلّ أَبِيب – يَافَا, translit=Tall ʾAbīb-Yāfā, links=no), often referred to as just Tel Aviv, is the most populous city in the G ...

and Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

, and descended to near the surface of the Dead Sea

The Dead Sea ( he, יַם הַמֶּלַח, ''Yam hamMelaḥ''; ar, اَلْبَحْرُ الْمَيْتُ, ''Āl-Baḥrū l-Maytū''), also known by other names, is a salt lake bordered by Jordan to the east and Israel and the West Bank ...

, below sea level. The ship delivered 16,000 letters in mail drops at Jaffa

Jaffa, in Hebrew Yafo ( he, יָפוֹ, ) and in Arabic Yafa ( ar, يَافَا) and also called Japho or Joppa, the southern and oldest part of Tel Aviv-Yafo, is an ancient port city in Israel. Jaffa is known for its association with the b ...

, Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates ...

, Budapest

Budapest (, ; ) is the capital and most populous city of Hungary. It is the ninth-largest city in the European Union by population within city limits and the second-largest city on the Danube river; the city has an estimated population ...

and Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

. The Egyptian government (under pressure from Britain) refused it permission to enter their airspace. The second Mediterranean cruise flew over France, Spain, Portugal and Tangier

Tangier ( ; ; ar, طنجة, Ṭanja) is a city in northwestern Morocco. It is on the Moroccan coast at the western entrance to the Strait of Gibraltar, where the Mediterranean Sea meets the Atlantic Ocean off Cape Spartel. The town is the cap ...

,

then returned home via Cannes

Cannes ( , , ; oc, Canas) is a city located on the French Riviera. It is a communes of France, commune located in the Alpes-Maritimes departments of France, department, and host city of the annual Cannes Film Festival, Midem, and Cannes Lions I ...

and Lyon

Lyon,, ; Occitan: ''Lion'', hist. ''Lionés'' also spelled in English as Lyons, is the third-largest city and second-largest metropolitan area of France. It is located at the confluence of the rivers Rhône and Saône, to the northwest of t ...

on 23–25 April.

Forced landing in France (1929)

On 16 May 1929, on the first night of its second trip to the US, ''Graf Zeppelin'' lost four of its engines. With Eckener struggling for a suitable place to force-land, the French Air Ministry allowed him to land at Cuers-Pierrefeu, near

On 16 May 1929, on the first night of its second trip to the US, ''Graf Zeppelin'' lost four of its engines. With Eckener struggling for a suitable place to force-land, the French Air Ministry allowed him to land at Cuers-Pierrefeu, near Toulon

Toulon (, , ; oc, label= Provençal, Tolon , , ) is a city on the French Riviera and a large port on the Mediterranean coast, with a major naval base. Located in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region, and the Provence province, Toulon is th ...

. Barely able to control the ship, Eckener made an emergency landing. The incident, and the forced comradeship it engendered, softened France's attitude to Germany and its airships slightly. The incident was caused by adjustments that had been made by the chief engineer to the four engines that failed.

On 4 August, the airship made it to Lakehurst on the second attempt. Aboard was Susie, an eastern gorilla

The eastern gorilla (''Gorilla beringei'') is a critically endangered species of the genus ''Gorilla'' and the largest living primate. At present, the species is subdivided into two subspecies. There are 3,800 eastern lowland gorillas or Graue ...

who had been captured near Lake Kivu

Lake Kivu is one of the African Great Lakes. It lies on the border between the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Rwanda, and is in the Albertine Rift, the western branch of the East African Rift. Lake Kivu empties into the Ruzizi River, whic ...

in the Belgian Congo

The Belgian Congo (french: Congo belge, ; nl, Belgisch-Congo) was a Belgian colony in Central Africa from 1908 until independence in 1960. The former colony adopted its present name, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), in 1964.

Colo ...

and sold by her German owner to an American dealer. After a touring career in the US, Susie went to Cincinnati Zoo in 1931, where she died in 1947.

Round-the-world flight (1929)

The American newspaper publisher

The American newspaper publisher William Randolph Hearst

William Randolph Hearst Sr. (; April 29, 1863 – August 14, 1951) was an American businessman, newspaper publisher, and politician known for developing the nation's largest newspaper chain and media company, Hearst Communications. His flamboya ...

's media empire paid half the cost of the project to fly ''Graf Zeppelin'' around the world, with four staff on the flight; Lady Hay Drummond-Hay, Karl von Wiegand, the Australian explorer Hubert Wilkins

Sir George Hubert Wilkins MC & Bar (31 October 188830 November 1958), commonly referred to as Captain Wilkins, was an Australian polar explorer, ornithologist, pilot, soldier, geographer and photographer. He was awarded the Military Cross afte ...

, and the cameraman Robert Hartmann. Drummond-Hay became the first woman to circumnavigate the world by air.

Hearst stipulated that the flight in August 1929 officially start and finish at Lakehurst. Round-the-world tickets were sold for almost $3000 (), but most participants had their costs paid for them. The flight's expenses were offset by the carriage of souvenir mail between Lakehurst, Friedrichshafen, Tokyo

Tokyo (; ja, 東京, , ), officially the Tokyo Metropolis ( ja, 東京都, label=none, ), is the capital and largest city of Japan. Formerly known as Edo, its metropolitan area () is the most populous in the world, with an estimated 37.468 ...

, and Los Angeles. A US franked letter flown on the whole trip from Lakehurst to Lakehurst required $3.55 () in postage.

''Graf Zeppelin'' set off from Lakehurst on 8 August, heading eastwards. The ship refuelled at Friedrichshafen, then continued across Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union to Tokyo. After five days at a former German airship shed that had been removed from Jüterbog

Jüterbog () is a historic town in north-eastern Germany, in the Teltow-Fläming district of Brandenburg. It is on the Nuthe river at the northern slope of the Fläming hill range, about southwest of Berlin.

History

The Slavic settlement of ' ...

and rebuilt at Kasumigaura Naval Air Station, ''Graf Zeppelin'' continued across the Pacific to California. Eckener delayed crossing the coast at San Francisco's Golden Gate

The Golden Gate is a strait on the west coast of North America that connects San Francisco Bay to the Pacific Ocean. It is defined by the headlands of the San Francisco Peninsula and the Marin Peninsula, and, since 1937, has been spanned by t ...

so as to come in near sunset for aesthetic effect. The ship landed at Mines Field

Los Angeles International Airport , commonly referred to as LAX (with each letter pronounced individually), is the primary international airport serving Los Angeles, California and its surrounding metropolitan area. LAX is located in the ...

in Los Angeles, completing the first ever nonstop flight across the Pacific Ocean. The takeoff from Los Angeles was difficult because of high temperatures and an inversion layer. To lighten the ship, six crew were sent on to Lakehurst by aeroplane. The airship suffered minor damage from a tail strike

In aviation, a tailstrike or tail strike occurs when the tail or empennage of an aircraft strikes the ground or other stationary object. This can happen with a fixed-wing aircraft with tricycle undercarriage, in both takeoff where the pilot rota ...

and barely cleared electricity cables at the edge of the field. The ''Graf Zeppelin'' arrived back at Lakehurst from the west on the morning of 29 August, three weeks after it had departed to the east.

Flying time for the four Lakehurst to Lakehurst legs was 12 days, 12 hours, and 13 minutes; the entire circumnavigation (including stops) took 21 days, 5 hours, and 31 minutes to cover . It was the fastest circumnavigation

Circumnavigation is the complete navigation around an entire island, continent, or astronomical object, astronomical body (e.g. a planet or natural satellite, moon). This article focuses on the circumnavigation of Earth.

The first recorded circ ...

of the globe at the time.

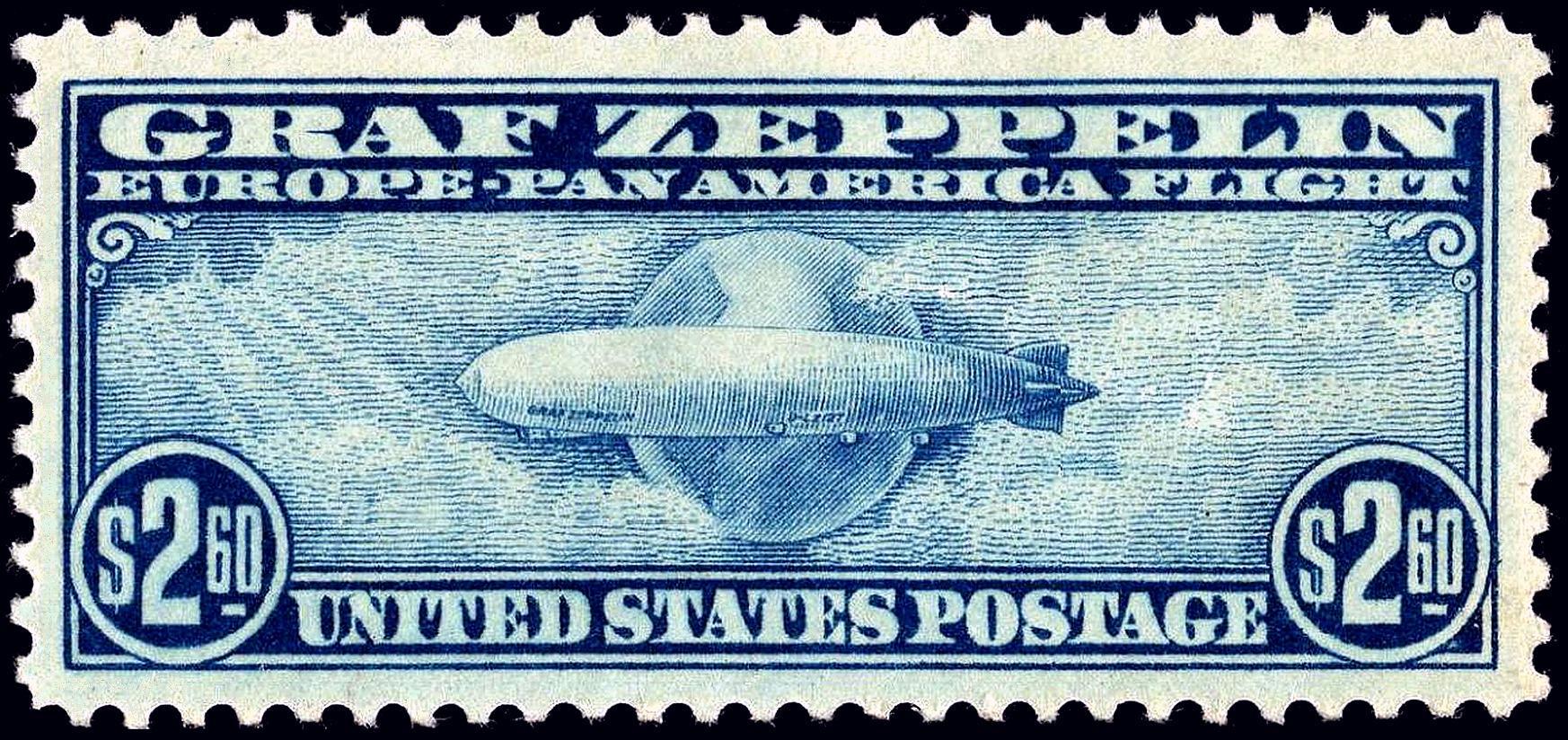

Eckener became the tenth recipient and the third aviator to be awarded the Gold Medal of the National Geographic Society

The National Geographic Society (NGS), headquartered in Washington, D.C., United States, is one of the largest non-profit scientific and educational organizations in the world.

Founded in 1888, its interests include geography, archaeology, and ...

, which he received on 27 March 1930 at the Washington Auditorium. Before returning to Germany, Eckener met President Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover (August 10, 1874 – October 20, 1964) was an American politician who served as the 31st president of the United States from 1929 to 1933 and a member of the Republican Party, holding office during the onset of the Gr ...

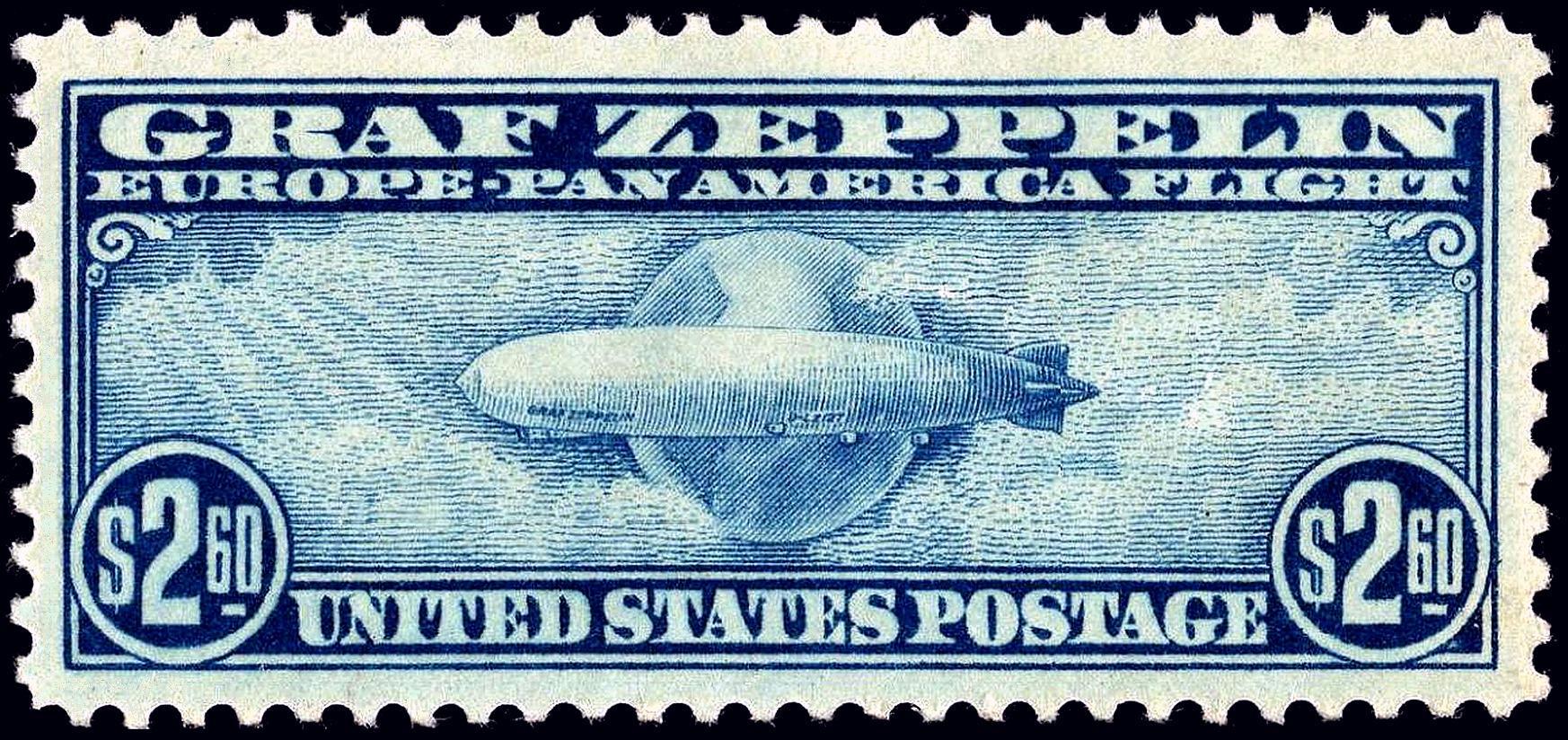

, and successfully lobbied the US Postmaster General for a special three-stamp issue (C-13, 14 & 15) for mail to be carried on the Europe-Pan American flight due to leave Germany in mid-May. Germany issued a commemorative coin celebrating the circumnavigation.

Europe-Pan American flight (1930)

On 26 April 1930, ''Graf Zeppelin'' flew low over the

On 26 April 1930, ''Graf Zeppelin'' flew low over the FA Cup Final

The FA Cup Final, commonly referred to in England as just the Cup Final, is the last match in the Football Association Challenge Cup. It has regularly been one of the most attended domestic football events in the world, with an official atten ...

at Wembley Stadium

Wembley Stadium (branded as Wembley Stadium connected by EE for sponsorship reasons) is a football stadium in Wembley, London. It opened in 2007 on the site of the Wembley Stadium (1923), original Wembley Stadium, which was demolished from 200 ...

in England, dipping in salute to King George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until Death and state funeral of George V, his death in 1936.

Born duri ...

, then briefly moored alongside the larger R100

His Majesty's Airship R100 was a privately designed and built British rigid airship made as part of a two-ship competition to develop a commercial airship service for use on British Empire routes as part of the Imperial Airship Scheme. The ot ...

at Cardington. On 18 May, it left on a triangular flight between Spain, Brazil, and the US, carrying 38 passengers, many of them in crew accommodation. The ship arrived at Recife

That it may shine on all ( Matthew 5:15)

, image_map = Brazil Pernambuco Recife location map.svg

, mapsize = 250px

, map_caption = Location in the state of Pernambuco

, pushpin_map = Brazil#South A ...

(Pernambuco) in Brazil, docking at Campo do Jiquiá on 22 May, where 300 soldiers helped land it. It then flew to Rio de Janeiro

Rio de Janeiro ( , , ; literally 'River of January'), or simply Rio, is the capital of the state of the same name, Brazil's third-most populous state, and the second-most populous city in Brazil, after São Paulo. Listed by the GaWC as a b ...

, where there was no post to tether to, so it was held down by the landing party for the two hours of the visit.

It flew north, via Recife, to Lakehurst; a storm damaged the rear engine nacelle, which had to be repaired in the hangar at Lakehurst. During ground handling of the airship there, it suddenly lifted, causing serious injury to one of the US Marines

The United States Marine Corps (USMC), also referred to as the United States Marines, is the maritime land force service branch of the United States Armed Forces responsible for conducting expeditionary and amphibious operations through combi ...

who was assisting. A few hours from home, when the ''Graf Zeppelin'' flew through a heavy hailstorm over the Saône

The Saône ( , ; frp, Sona; lat, Arar) is a river in eastern France. It is a right tributary of the Rhône, rising at Vioménil in the Vosges department and joining the Rhône in Lyon, at the southern end of the Presqu'île.

The name ...

, the envelope was damaged and the ship lost lift. Eckener ordered full power and flew the ship out of trouble, but it came within 200 feet of hitting the ground.

The Europe-Pan American flight was largely funded by the sale of special stamps issued by Spain, Brazil, and the US for franking mail carried on the trip. The US issued stamps in three denominations: 65¢, $1.30, and $2.60, all on 19 April 1930.

Middle East flight (1931)

The second flight to the Middle East took place in 1931, beginning on 9 April. ''Graf Zeppelin'' crossed the Mediterranean to Benghazi in Libya, then flew viaAlexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandria ...

, to Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo metro ...

in Egypt, where it saluted King Fuad at the Qubbah Palace, then visited the Great Pyramid of Giza

The Great Pyramid of Giza is the biggest Egyptian pyramid and the tomb of Fourth Dynasty pharaoh Khufu. Built in the early 26th century BC during a period of around 27 years, the pyramid is the oldest of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient Worl ...

and hovered 70 feet above the top of the monument. After a brief stop, the ship flew to Palestine where it circled Jerusalem, then returned to Cairo to pick up Eckener, who had stayed for an audience with the King. It returned to Friedrichshafen on 13 April.

Polar flight (1931)

The polar flight (''Polarfahrt 1931'') lasted from 24 to 31 July 1931. The ship rendezvoused with the Soviet icebreaker ''Malygin'', which had the Italian polar explorer

The polar flight (''Polarfahrt 1931'') lasted from 24 to 31 July 1931. The ship rendezvoused with the Soviet icebreaker ''Malygin'', which had the Italian polar explorer Umberto Nobile

Umberto Nobile (; 21 January 1885 – 30 July 1978) was an Italian aviator, aeronautical engineer and Arctic explorer.

Nobile was a developer and promoter of semi-rigid airships in the years between the two World Wars. He is primarily remembe ...

aboard. It exchanged of souvenir mail with the airship, which Eckener landed on the Arctic Ocean

The Arctic Ocean is the smallest and shallowest of the world's five major oceans. It spans an area of approximately and is known as the coldest of all the oceans. The International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) recognizes it as an ocean, a ...

. Fifty thousand cards and letters, weighing , were flown. The costs of the expedition were met largely by the sale of special postage stamps issued by Germany and the Soviet Union to frank

Frank or Franks may refer to:

People

* Frank (given name)

* Frank (surname)

* Franks (surname)

* Franks, a medieval Germanic people

* Frank, a term in the Muslim world for all western Europeans, particularly during the Crusades - see Farang

Curr ...

the mail carried on the flight.

The writer Arthur Koestler

Arthur Koestler, (, ; ; hu, Kösztler Artúr; 5 September 1905 – 1 March 1983) was a Hungarian-born author and journalist. Koestler was born in Budapest and, apart from his early school years, was educated in Austria. In 1931, Koestler join ...

was one of two journalists on board, along with a multinational team of scientists led by the Soviet Professor Samoilowich, who measured the Earth's magnetic field

Earth's magnetic field, also known as the geomagnetic field, is the magnetic field that extends from Earth's interior out into space, where it interacts with the solar wind, a stream of charged particles emanating from the Sun. The magnetic f ...

, and a Soviet radio operator. The expedition photographed and mapped Franz Josef Land

Franz Josef Land, Frantz Iosef Land, Franz Joseph Land or Francis Joseph's Land ( rus, Земля́ Фра́нца-Ио́сифа, r=Zemlya Frantsa-Iosifa, no, Fridtjof Nansen Land) is a Russian archipelago in the Arctic Ocean. It is inhabited on ...

accurately for the first time, and came within of the North Pole

The North Pole, also known as the Geographic North Pole or Terrestrial North Pole, is the point in the Northern Hemisphere where the Earth's axis of rotation meets its surface. It is called the True North Pole to distinguish from the Mag ...

. It deployed three early radiosonde

A radiosonde is a battery-powered telemetry instrument carried into the atmosphere usually by a weather balloon that measures various atmospheric parameters and transmits them by radio to a ground receiver. Modern radiosondes measure or calcula ...

s over the Arctic to collect meteorological data from the upper atmosphere.

South American operations (1931–1937)

From the beginning, Luftschiffbau Zeppelin had plans to serve South America. There was a large community of Germans in Brazil, and existing sea connections were slow and uncomfortable. ''Graf Zeppelin'' could transport passengers over long distances in the same luxury as an ocean liner, and almost as quickly as contemporary airliners.

''Graf Zeppelin'' made three trips to Brazil in 1931 and nine in 1932. The route to Brazil meant flying down the Rhône valley in France, a cause of great sensitivity between the wars. The French government, concerned about espionage, restricted it to a -wide corridor in 1934. ''Graf Zeppelin'' was too small and slow for the stormy North Atlantic route, but because of the Blau gas fuel, could carry out the longer South Atlantic service. On 2 July 1932 it flew a 24-hour tour of Britain.

From the beginning, Luftschiffbau Zeppelin had plans to serve South America. There was a large community of Germans in Brazil, and existing sea connections were slow and uncomfortable. ''Graf Zeppelin'' could transport passengers over long distances in the same luxury as an ocean liner, and almost as quickly as contemporary airliners.

''Graf Zeppelin'' made three trips to Brazil in 1931 and nine in 1932. The route to Brazil meant flying down the Rhône valley in France, a cause of great sensitivity between the wars. The French government, concerned about espionage, restricted it to a -wide corridor in 1934. ''Graf Zeppelin'' was too small and slow for the stormy North Atlantic route, but because of the Blau gas fuel, could carry out the longer South Atlantic service. On 2 July 1932 it flew a 24-hour tour of Britain.

While returning from Brazil in October 1933, ''Graf Zeppelin'' stopped at NAS Opa Locka in Miami, Florida, and then

While returning from Brazil in October 1933, ''Graf Zeppelin'' stopped at NAS Opa Locka in Miami, Florida, and then Akron, Ohio

Akron () is the fifth-largest city in the U.S. state of Ohio and is the county seat of Summit County. It is located on the western edge of the Glaciated Allegheny Plateau, about south of downtown Cleveland. As of the 2020 Census, the city prop ...

, where it moored at the Goodyear Zeppelin airdock. The airship then appeared at the Century of Progress

A Century of Progress International Exposition, also known as the Chicago World's Fair, was a world's fair held in the city of Chicago, Illinois, United States, from 1933 to 1934. The fair, registered under the Bureau International des Expositi ...

World's Fair in Chicago. It displayed swastika

The swastika (卐 or 卍) is an ancient religious and cultural symbol, predominantly in various Eurasian, as well as some African and American cultures, now also widely recognized for its appropriation by the Nazi Party and by neo-Nazis. It ...

markings on the left side of the fins, as the Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right politics, far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that crea ...

had taken power in January. Eckener circled the fair clockwise so that the swastikas would not be seen by the spectators. The United States Post Office Department

The United States Post Office Department (USPOD; also known as the Post Office or U.S. Mail) was the predecessor of the United States Postal Service, in the form of a Cabinet department, officially from 1872 to 1971. It was headed by the postma ...

issued a special 50-cent airmail stamp (C-18) for the visit, which was the fifth and final one the ship made to the US.

The airship's cotton envelope absorbed moisture from the air in humid tropical conditions. When the

The airship's cotton envelope absorbed moisture from the air in humid tropical conditions. When the relative humidity

Humidity is the concentration of water vapor present in the air. Water vapor, the gaseous state of water, is generally invisible to the human eye. Humidity indicates the likelihood for precipitation, dew, or fog to be present.

Humidity dep ...

reached 90%, the ship's weight rose by almost . Exposure to tropical downpours could greatly add to this, but when under way the ship had enough reserve power to generate dynamic lift to compensate. In April 1935 it made a rough forced landing at Recife after it was caught in a rainstorm at low speed on the approach to land and the added weight of several tons of water caused it to sink to the ground. The lower rudder was lost, the outer envelope was ripped in several places, and a petrol tank was punctured by a palm tree.

In late 1935 ''Graf Zeppelin'' operated a temporary postal shuttle service between Recife and Bathurst, in the British African colony of the Gambia. On 24 November, during the second trip, the crew learned of an insurrection in Brazil, and there was some doubt whether it would be possible to return to Recife. ''Graf Zeppelin'' delivered its mail to

In late 1935 ''Graf Zeppelin'' operated a temporary postal shuttle service between Recife and Bathurst, in the British African colony of the Gambia. On 24 November, during the second trip, the crew learned of an insurrection in Brazil, and there was some doubt whether it would be possible to return to Recife. ''Graf Zeppelin'' delivered its mail to Maceió

Maceió (), formerly sometimes Anglicised as Maceio, is the capital and the largest city of the coastal state of Alagoas, Brazil. The name "Maceió" is an Indigenous term for a spring. Most maceiós flow to the sea, but some get trapped and form l ...

, then loitered off the coast for three days until it was safe to land, after a flight of 118 hours and 40 minutes.

Brazil built a hangar for airships at Bartolomeu de Gusmão Airport, near Rio de Janeiro, at a cost of $1 million (equivalent to $ million in 2018 ). Brazil charged the DZR $2000 ($) per landing, and had agreed that German airships would land there 20 times per year, to pay off the cost. The hangar was constructed in Germany and the parts were transported and assembled on site. It was finished in late 1936, and was used four times by ''Graf Zeppelin'' and five by ''Hindenburg''. It now houses units of the Brazilian Air Force.

''Graf Zeppelin'' made 64 round trips to Brazil, on the first regular intercontinental commercial air passenger service, and it continued until the loss of the ''Hindenburg'' in May 1937.

Brazil built a hangar for airships at Bartolomeu de Gusmão Airport, near Rio de Janeiro, at a cost of $1 million (equivalent to $ million in 2018 ). Brazil charged the DZR $2000 ($) per landing, and had agreed that German airships would land there 20 times per year, to pay off the cost. The hangar was constructed in Germany and the parts were transported and assembled on site. It was finished in late 1936, and was used four times by ''Graf Zeppelin'' and five by ''Hindenburg''. It now houses units of the Brazilian Air Force.

''Graf Zeppelin'' made 64 round trips to Brazil, on the first regular intercontinental commercial air passenger service, and it continued until the loss of the ''Hindenburg'' in May 1937.

Propaganda (1936)

Eckener was outspoken about his dislike of the Nazi Party, and was warned about it byRudolf Diels

Rudolf Diels (16 December 1900 – 18 November 1957) was a German civil servant and head of the Gestapo in 1933–34. He obtained the rank of SS-'' Oberführer'' and was a protégé of Hermann Göring.

Early life

Diels was born in Berghausen i ...

, the head of the Gestapo

The (), abbreviated Gestapo (; ), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of Prussia into one organi ...

. When the Nazis gained power in 1933, Joseph Goebbels (Reich Minister of Propaganda) and Hermann Göring

Hermann Wilhelm Göring (or Goering; ; 12 January 1893 – 15 October 1946) was a German politician, military leader and convicted war criminal. He was one of the most powerful figures in the Nazi Party, which ruled Germany from 1933 to 1 ...

(Commander-in-chief of the Luftwaffe) sidelined Eckener by putting the more sympathetic Lehmann in charge of a new airline, Deutsche Zeppelin Reederei

Deutsche Zeppelin-Reederei (), abbreviated DZR, is a German limited-liability company that operates commercial passenger zeppelin flights. The current incarnation of the DZR was founded in 2001 and is based in Friedrichshafen. It is a subsidiary ...

(DZR), which operated German airships.

On 7 March 1936, in violation of the Treaty of Versailles and the Locarno Treaties, German troops reoccupied the Rhineland. Hitler called a plebiscite for 29 March to retrospectively approve the reoccupation, and adopt a list of exclusively Nazi candidates to sit in the new Reichstag. Goebbels commandeered ''Graf Zeppelin'' and the newly launched ''Hindenburg'' for the Reich Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda

The Reich Ministry for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda (; RMVP), also known simply as the Ministry of Propaganda (), controlled the content of the press, literature, visual arts, film, theater, music and radio in Nazi Germany.

The ministry ...

. The airships flew in tandem around Germany before the vote, with a joint departure from Löwenthal on the morning of 26 March. They toured the country for four days and three nights, dropping propaganda leaflets, playing martial music and slogans from large loudspeakers, and broadcasting political speeches from a makeshift radio studio on ''Hindenburg''.

Retirement and aftermath

The crew heard of the ''Hindenburg'' disaster by radio on 6 May 1937 while in the air, returning from Brazil to Germany; they delayed telling the passengers until after landing on 8 May so as not to alarm them. The disaster, in which Lehmann and 35 others were killed, destroyed public faith in the safety of hydrogen-filled airships, making continued passenger operations impossible unless they could convert to non-flammablehelium

Helium (from el, ἥλιος, helios, lit=sun) is a chemical element with the symbol He and atomic number 2. It is a colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-toxic, inert, monatomic gas and the first in the noble gas group in the periodic table. ...

. ''Hindenburg'' had originally been planned to use helium, but almost all of the world's supply was controlled by the US, and its export had been tightly restricted by the Helium Act of 1925

Helium Act of 1925, 50 USC § 161, is a United States statute drafted for the purpose of conservation, exploration, and procurement of helium gas. The Act of Congress authorized the condemnation, lease, or purchase of acquired lands bearing the p ...

.

''Graf Zeppelin'' was permanently withdrawn from service shortly after the disaster. On 18 June, its 590th and last flight took it to Frankfurt am Main, where it was deflated and exhibited to visitors in its hangar. President Roosevelt supported exporting enough helium for the ''Hindenburg''-class LZ 130 ''Graf Zeppelin II'' to resume commercial transatlantic passenger service by 1939, but by early 1938, the opposition of Interior Secretary

The United States secretary of the interior is the head of the United States Department of the Interior. The secretary and the Department of the Interior are responsible for the management and conservation of most federal land along with natural ...

Harold Ickes, who was concerned that Germany was likely to use the airship in war, made that impossible. On 11 May 1938, Roosevelt's press secretary announced that the US would not sell helium to Germany. Eckener, who had unsuccessfully intervened, responded that it would be "the death sentence for commercial lighter-than-air craft." ''Graf Zeppelin II'' made 30 test, promotional, propaganda and military surveillance flights around Europe using hydrogen between September 1938 and August 1939; it never entered commercial passenger service. On 4 March 1940, Göring ordered ''Graf Zeppelin'' and ''Graf Zeppelin II'' to be scrapped, and their airframes to be melted down for the German military aircraft industry.

During its career, ''Graf Zeppelin'' had flown almost 1.7 million km (1,053,391 miles), the first aircraft to fly over a million miles. It made 144 oceanic crossings (143 across the Atlantic, and one of the Pacific), carried 13,110 passengers and of mail and freight. It flew for 17,177 hours (717 days, or nearly two years), without injuring a passenger or crewman. It has been called "the world's most successful airship", but it was not a commercial success; it had been hoped that the ''Hindenburg''-class airships that followed would have the capacity and speed to make money on the popular North Atlantic route. ''Graf Zeppelin''Focke-Wulf Condor